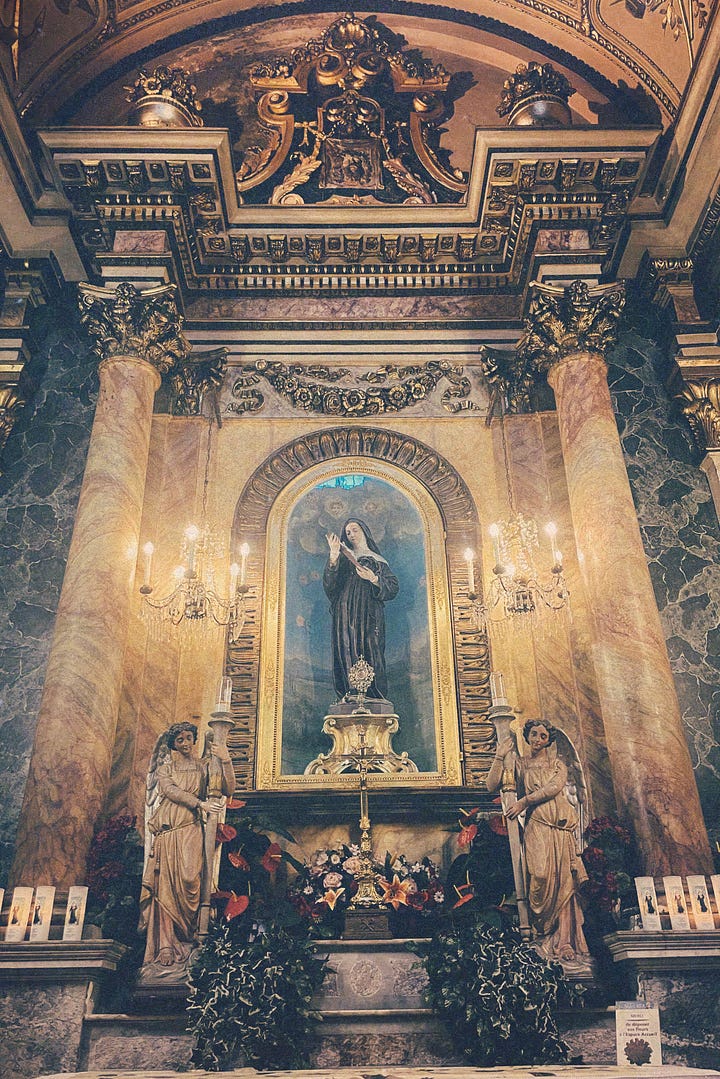

I spend my mornings in the sea, and my afternoons crying among the cool stone pillars of Ste. Rita’s church.

It's June 2022 and I’m in Nice, France. I don’t know what’s going to happen next.

All I know, now, is the smell of iodine and damp rock and incense. All I can feel is hot sun and sadness and sometimes a glimmer of hope, like I’ve swallowed the sun glints that play on the water. Mostly, though, I am trying not to drown in myself.

My mom died. I've barely talked about it.

Because people have their own problems to worry about and therapy is only 50 minutes a week.

So I float in the mornings like I’m back in the womb, and then I sob because the womb I called home is gone now.

After a particularly vicious cry session with Ste. Rita—pink cheeks, pink roses, beatific in her stillness—I take inspiration and stop for a glass of rosé. I need the drops of cold condensation against my fingertips, to erase the memory of hot tears on my cheeks.

And anyway, even silent tears make you dehydrated, especially in this weather.

They look at me across a sidewalk polka-dotted with small round tables. The obviously weird one and the slightly less weird one.

I’m journaling and they ask if I’m a writer. I am. The one weirdo? He’s a painter. (This is not surprising.) The other? Also a writer. Denizens of Vieux Nice: not immune to the summer crowds of boisterous, burnt Brits and sock-wearing Germans but rather impervious to it all.

“I rent out my home in the summer,” says the writer, “and move to a cheaper place nearby. They’ll all be gone in two months, and I’ll have more money than before.”

I’ll be gone soon, too, like all the rest of them.

I don’t know where I’ll land, but every ringing of Cathedrale Sainte-Réparate's bells pounds in my chest like a twin heartbeat, the rhythm of time passing. My time here, passing away.

We have coffee together one morning, the writer and I, looking out over Plage de Ponchettes. Noses in our notebooks, we speak more about writing than ourselves, and sit in silence more than we speak.

In the blue of that evening, or some other—who knows in the salted-honey haze of the Côte d’Azur—we walk arm in arm along the Quai, coursing with crowds still sun-drunk despite the deepening sky.

We sit on a boulder and watch the full Strawberry Moon suspended over black water. Rose-gold reflections scatter across the bay, dancing like living light, dancing to noughties-era GIMS on someone's boombox.

The writer pulls out a phone and opens YouTube. Proffers an earbud. GIMS & co. walk on, and Benny Goodman's band begins to play a slow tune, just for us.

Something delicate and dry brushes my cheek; a hummingbird-wing of a kiss.

But I don’t want to be kissed. I want to float in the water and cry in the church and be allowed to miss my mom.

A new and tentative chord strums in my ear. A question made music.

Moon River, wider than a mile, I’m crossing you in style some day.

Audrey’s voice is ephemeral like it’s about to dissolve, or to crumple like a petal crushed underfoot, leaving only a perfume memory of its brief and soft existence.

The song choice is a little on the nose, not very creative for a writer. But the intentions are good.

Of course, he doesn’t know it was my mother’s favorite song.

I still haven’t cried enough to talk about her. I still have a sea’s worth of tears inside me before I can do that. Before I can make even a passing reference without my whole self breaking.

I sit as still as possible, watching the shattered moonlight. Watching the red summer moon ripen as it sinks.

Grief stalks me like a tiger.

If I move—if I even breathe too deeply—it will catch me and this time it might kill me. I am already striped by the scars of our previous encounters. This time I might not put myself back together again. I might bleed out, might break forever like light on water.

I think of the statue of Ste. Rita with her roses: solid, glossy, placid. I imagine I am made of something solid, no room inside for roiling despair, no muscles to twitch and catch grief’s predator eye.

Two drifters, off to see the world. There’s such a lot of world to see.

She never saw the Mediterranean. Never saw France, or the old cathedrals that smell like wet stone and incense.

And I can’t tell her about it. I can’t call her and tell her what I’ve seen or my triumphs or all the bad things that have happened since she went away.

Here I am in paradise and I spend my afternoons hidden away sobbing as quietly as possible so as not to disturb the other tourists with their lovers or families, sharing this brief and lovely summer together.

I suddenly feel hot. Not from the humidity settling like a blanket or the little birdlike affections still darting along my carved-wood exterior.

It’s shame.

I am so ashamed of myself. For grieving still, for not grieving sooner, for being an impatient and petulant daughter who ignores phone calls and skips holidays.

For not enjoying what life I have left because that’s what she would want and I can’t even love myself in tribute to her.

The song ends. A small mercy for me.

I feel grief pad off; I’ll be able to move again soon. But it has my scent (had it for a while now) and I know I am its prey in perpetuity.

The moon drops off the vine and the horizon disappears into the dark. No heavy sweetness remains, no luminous river of light. The moment, such as it was, is over.

My statue act has exhausted me (it always does) and I’m ready to be alone. Not so heartbreaking, aloneness, as hiding grief’s claw marks from those who should have offered a balm.

Tomorrow morning I’ll swim again. I’ll dip my face in the cool water and look out into the blue. Perhaps I will share a few tears with the sea before I descend into the church again.

And when I’m ready to let grief catch me again, "Moon River" will be waiting.

If you enjoy my stories and photographs, please consider donating to my camera fund.

This was such a beautiful ode to your mom and to grief 🩵